Eric Mazur:

Welcome to the Social Learning Amplified podcast, the podcast that brings us candid conversations with educators. We're finding new ways to engage and motivate their students inside and outside the classroom. Each episode of Social Learning Amplified will give you real life examples and practical strategies you can put into practice in your own courses. Let's meet today's guest. Thank you for joining us today for this episode on empowering Active Learning in the Social Learning Amplified podcast series. I'm your host, Eric Mazur, and our guest today is Dr. Michelle Miller. Thank you for being here today.

Dr. Michelle D. Miller:

Oh, thank you. It's so fun to be here today as well.

Eric Mazur:

Today's episode is connected to a book event held on Perusall. More about that event later. The book in question authored by our guest is Remembering and Forgetting in the Age of Technology, which was published by West Virginia University Press in April, 2022. The subtitle of the book is Teaching Learning and the Science of Memory in a Wired World. I just love that title. I tend to be forgetful, and I've learned to use the scaffolding of technology to offload the less important facts and memories so I can focus on the important mental models. But before we dive into the book, let me start by telling you a bit about our guest and leaders who care about learning. Dr. Michelle Miller is a cognitive psychologist, researcher, and speaker focused on supporting and inspiring teachers, instructional designers and leaders who care about learning. She advocates for building learning experiences based on research on how people learn and for using educational technologies in ways that align with those principles of learning.

She's the author of several books, including Minds Online Teaching Effectively with Technology from Harvard University Press, and Remembering and Forgetting in the Age of Technology, which is the topic of today. She has a new book coming out in the fall of this year entitled A Teacher's Guide to Learning Students' Names: Why You Should, why It's Hard, and How You Can. Dr. Miller completed her PhD in cognitive Psychology and Behavioral neuroscience at UCLA. She currently serves as professor of psychological sciences and president's Distinguished Teaching fellow at Northern Arizona University. I just love the research-based approach. You're taking your book and how you balance, shall I call it? We don't need to remember anything anymore attitude. Some people hold with the we should ban technology from the classroom. Others advocate for, let's start with the science of memory. I want to go from the science and research to the more practical aspects as we go through this podcast. What should all instructors in your opinion know about how memory works?

Dr. Michelle D. Miller:

Oh, this question just opens up so much for a memory scientist like myself. And I mean, your comment is right from the top of our podcast. I mean, they point out that right away. I mean, most of us had thought about memory in some way or another, oftentimes in a kind of negative context, or we have these expectations that it should work a certain way and time and again, it doesn't work that way and we're disappointed. And so that really does connect us into the research and the sorts of things that I get so excited to share as somebody who's dipped in and out of memory as a research topic throughout my career. And definitely now that I do so much applied work with my fellow faculty. So what if I could just wave the wand and say everybody has this knowledge, what would that look like?

Well, one of the things that I would probably start with actually ties into one of the commonest misconceptions about memory. And actually as I talk about in the book, this has been studied in the general population in the United States at least. And I've also had the pleasure of collaborating with a great research team. We looked at some of the beliefs about cognition among instructors and others involved in higher education. And this common misconception is that we walk around with kind of a GoPro in the head, sort of this invisible security camera that's running all the footage and hey, if I want to know what happened, I just rewind the tape and Hansen, Hansen, there we are. And nothing could be farther from the truth that there's one thing we have learned from the last 30 or so years of memory research is that this is a very active process and a lot of kind of discretion goes on in memory and it is in no way resembles a recording device.

And so we could all look at that as sophisticated academics and say, oh yeah, I know that, but I think it sneaks in some subtle ways. So we say, well, I wrote something on the board for weeks straight, why didn't students pick that up in the GoPro in the head? Where did that information go? And I think too, it's also can be a case of sometimes a little bit of knowledge is a dangerous thing as the saying goes. And so even those who've had some exposure in the past, a cognitive theory or memory theory might think of memory not as a camera, but as something like an assembly line. Information comes in and it goes around in cycles. Sometimes we have those diagrams that have a little circle in the middle of like, oh, you rehearsed and then it ships off to long-term error. It makes it just sound like it's all very kind of predetermined.

And again, this doesn't capture the subtleties and this matters for learning. So instead of thinking of memory in these ways, I really encourage faculty to reflect and to think memory is a set of systems that our brains and our minds evolved in order to take in information that helps us survive and to do so very selectively and to do so in a way that will serve that information back up in the right context. So cues, things like that, those really, really matter for learning. So that's what I would really say to my fellow faculty. So there's a lot more than simple repetition. This is where, of course, active involvement and I'm sure we'll touch on things like retrieval practice and quizzing yourself and how important that is. So that's what I would share as an opening conversation with faculty if I could speak to every faculty member in the world.

Eric Mazur:

I see. So you mentioned the word knowledge when you start answering this question, and in your book too, you mentioned knowledge often in tandem with memory. So I would like to sort of clarify the distinction between those two and the connection between those two. I mean, if I think of Bloom's taxonomy, right? I mean I think memorization is at the top and then understanding which I would sort of consider maybe moving towards knowledge above memory where memory sort of remembering facts and knowledge is sort of understanding the connection between facts and so on to higher or levels of thinking. Is that the way you think about these two?

Dr. Michelle D. Miller:

I think so. I think you're really onto something, especially when you are implying here that when we say knowledge, whether it's in a more scientific context or in this more everyday intuitive way that we're going to use it, those interconnections, I mean we are still a long way from knowing exactly how memories are formed and how they're organized in the mind, especially within the brain, but as sort of basic concepts conceptualizations go, that idea of a network seems to be one that has been around for a long time, and I think it really serves us well. And so just moving away from the recorder concept is very helpful. Moving away from the idea that we sort of file things this big filing cabinet and you want to find something, look it up, it's like, no, it's as much more organic, sometimes messy, very interconnected set of things that we have saved in the mind and in the brain. And I mean in a way that's great. It also accounts for how memory can be part of creativity. One thing is connected to another, gets you thinking about another thing, and boom, now we have a new combination that's never really been thought about before. So I think that's appropriate.

The longer I work in sort of applied fields too, the less I sometimes get as worried as my more disciplinary colleagues of where's exactly the line of memory and knowledge. I mean, I guess you could say knowledge is made out of memories. I guess another kind of way of looking that term is knowledge is semantic memory. So again, as they talk about in the book and as many of your listeners will have already encountered before semantic memory, sort of our body of factual knowledge, and it also includes our vocabulary, and that can be distinguished from episodic memories, which is our autobiographical. Like I was there and I remember the feelings of being there in a context and procedural memory, which is how to do something like I'm an avid knitter, I know how to knit. We may not think of that as a memory or as knowledge, but just knowing how to manipulate the yarn in my fingers that is tapping into a form of memory. So those are some distinctions I think are relevant.

Eric Mazur:

Right. And you said something else. I forgot exactly what it was that triggered that, but in some sense, knowledge can affect memory. Of course, maybe eventually we'll get back to practice retrieval and the rewriting of memories. But I remember, and we were inspired by this research study by a thesis that was published at the University of Washington to essentially that showed that students often incorrectly remembered the outcome of a classroom demonstration depending on their conceptual model of the demonstration itself. So we did, I think this is one of my most highly cited papers in education, we decided to do a systematic study where we did classroom demonstrations and then presented them in different ways. One is just do your best possible job presenting and others, where we had students think about the demonstration first, predict the outcome, and then if the outcome and then observe the demonstration, if the outcome was not consistent with their prediction, they had to discuss it with their neighbors and try to resolve the discrepancy.

And we found something really interesting. We found that the students who had seen the classroom demonstration but not really had any time to think it over, because you're at the mercy of the pace of the instructor, often incorrectly remembered the outcome. In fact, we have at least one evidence of a student writing as shown in class, blah, blah, blah, where the blah blah blah was exactly the opposite of what happened and precisely the misconception we want to unseat. And I was really surprised about that. But then a cognitive psychologist at Harvard pointed out to me that the way we store facts in our brains is essentially by mental models. So if you have the wrong mental model in your head and you see something, you adjust your memory to the wrong mental model rather than correcting the mental model based on the facts you see. And now that I think of it, advertisements, trial lawyers, I mean they exploit that all the time. Of course. So it's an interesting interplay between memory and mental models.

Dr. Michelle D. Miller:

Oh my goodness. And I love the way that you've unpacked that and described it, and how does it come back to the classroom? It absolutely does. I mean, you can say like, oh, I don't worry about memory or memorization of my classes, but this is what's going on. Students have, as you mentioned, assumptions. They have models. They have things they've been told before about themselves or about this subject, the class that they took last semester that's different than what their neighbor took the previous semester. And they do. They turn into models and that becomes maybe filters in exactly the right word, but that becomes a framework in into which we slot new information. And I mean, yeah, that can lead to I'm sure some real unanticipated consequences as again, if we think, well, I said it, students either recorded it or they didn't and then they replay it at the exam.

No way what they're doing, maybe they didn't take it in at all. Maybe they took in something different based on what was already there in that sort of network or framework of knowledge. And then at the time when they go to retrieve it, the cues that they get might bias them in a particular way. And as your colleague might've mentioned too, I mean there's that reconstruction process, which you're right, made a huge splash, especially in the field of forensic psychology. And people started saying, oh my gosh, the implications for jury trials and eyewitness testimony are absolutely enormous, that it's really more a process of sort of piecing together more or less complete product based on a kind of an incomplete set of pieces and a few pieces that snuck in there that never should have been in the first place. So there is that.

But here too, I mean, just one other little thing to share with faculty is to reflect and say, is this a flaw?

Is this a problem? Maybe not necessarily. If our brains and our minds are really set up to, again, be very selective, to take in what's going to be relevant, interpret it, only take in things that we can interpret the point of keeping something if we don't know what it means, and then bringing it back in that relevant context. Well, in that case, it sort of makes a little bit of sense. I would say, you know what? Here's a model that's served me well for years and years. I've always thought this and I'm going to keep thinking it, and so I'm going to hang on to things that sort of fit with that. So yeah, you're really getting that holistic view of just how messy and complicated the whole thing is.

Eric Mazur:

Absolutely. So going up Bloom's taxonomy in a sense, you say in your book that if I say it correctly here, that knowledge reinforces higher level thinking where some people think knowledge competes with it. Can you say more about the relationship between content knowledge and higher level thinking?

Dr. Michelle D. Miller:

Oh my goodness, I'm so glad that we are touching on this because this is the crucial thing. I mean, part of as I've been getting out there and talking to faculty, it just really struck me just how fraught an issue this is. I mean, I'm the cognitive psychologist. I'm like, memory is great. Let's talk about it. We know all these wonderful principles we can use. And there's a real subset of faculty who, I mean, they really seem offended when I said that. Like, oh my gosh, you're reinforcing this idea of just transferring knowledge from my head to your head, and it's a very hierarchical thing and I want higher learning. And haven't you ever heard of critical thinking and all that was coming from a good place? I don't mean to disparage any of that at all. In fact, I really love it when folks bring that sort of thing up because it opens these conversations.

So I think, yeah, that's something that I know I was kind of told and sold on as a beginning instructor of like, well, you can have one or the other. Do you want 'em to remember? Do you want critical thinking? And I always say yes, as a person, I always reject. I'm not very good at making these choices. So I've gone down that road. So getting back to that idea, I mean, it really is this reciprocal, mutually reinforcing relationship. I have absolutely come to believe that. And the more evidence rolls in, even since the book was published, the more I do believe that. So some of the research, for example, that's out there will look at the ability to say, you're learning to categorize things. You're learning about families of biological classes of animals in one of my favorite studies, and you've had more opportunity to frankly memorize the examples you've been given using more powerful recall techniques and techniques for reinforcing memory.

Well, if you've done that, you have a better ability to take a brand new example and say, you know what? I think it's over here. I think that's how to classify it, and here's why. And so I think these are these wonderful glimmers of we may not be able to measure all of higher thinking, at least not very well, not yet. But these areas, being able to draw inferences, transfer to new situations, I mean, that's kind of what new thing, what higher thinking is about, or at least in part. So seeing that, and at the same time as students grapple with more difficult conceptual questions as they look at those questions that have maybe not a definite answer that reinforces their memory for the information they were using. Daniel Willingham is probably the cognitive scientists and writers, he's put it better than anybody. He said, memory is the residue of thought. I mean, how cool is that? We remember our students, remember what they think about, and there's a huge line of research going back decades that actually reinforces willinghams points quite well. So it's not just his intuitions, although for many experienced teachers, that's exactly what we see. And I hope through reading about it and learning about the research, that they kind of double down on those powerful practices.

Eric Mazur:

I certainly like that quote, and I think that rhymes exceptionally well with practice retrieval, right? I mean, it's the act of retrieving that either rewrites or writes a memory, talking about memory. I certainly know that memory gets worse with age, and I rely heavily on technology to remember things that are not crucial to my life and that I'm not using very often. But I wonder is technology as we have it today, the sort of instant information, the instant access, pardon me, to information causing memory to get worse in your opinion? I don't know the answer to that question. I'm very curious.

Dr. Michelle D. Miller:

Yeah. Oh my goodness. And that is such a good question, and it is the one that really got me hooked into the idea of doing this book. I do want to take a little detour there. I do want to dress as memory gets worse as we get older here. Again, yes and no. It depends on what kind of memory we're talking about. When I was a graduate student, we studied older adults and we were looking at the psychology of language in particular. So yeah, the ability to pull up a particular word or name in particular does begin to drop off radically with age even when there's no underlying disease or problem. So it is not worrisome, but it's annoying. But vocabulary grows. So here's the irony, more words. Your memory is great in that way, but your ability to pick one out on any given occasion is worse.

So there's that. And older adults are also, we're better at sometimes seeing the connections between our items and that everything we know. So yeah, here again, there's nuance to it, but with technology, I mean this is such, I dunno about you, I've just seen some variation on this trope over and over of like, well, phones get smarter and we get dumber and it's destroying the brain. And a lot of that is connected to the issue of attention, which is of course a related issue, but it's exactly the same thing. So here's the thing, here's how I would respond.

We do have this moral panic. I talk about that a lot in the book too. This like, oh my gosh, we really build up with new technologies, how scary and damaging it is. And that just really seems to snowball. So caution is warranted. I don't think there's any reason to believe that across the board that our cognitive faculties, including memory have gotten worse as a function of this ubiquitous mobile technology. That said, there are some interesting consequences that are going on, and they think they do get back to that theme that our memories are hyper, hyper-efficient, right? We only want to save certain things. So one big thing I talk about in the book and I think is so fascinating is cognitive offloading. And that's a term that I think all of us, we hear that and we're like, okay, I know what you mean, but really this has been tracked in memory very precisely by one landmark study early on, and then it's been replicated a number of times, and it goes like this.

It says, when you think that you can look something back up online, like, well, I can always get back to that, right? Even if you do that unconsciously, which is the scary part, you're less likely to remember that on your own. You're more likely to remember where to find it, but less likely to remember that on its own. So I mean, it kind of again makes sense. Your brain's like, well, if I really don't need that, then why use it? And so you kind of think about if that's our students and they're sort of going along with that mentality over time, that could in theory accrue to less that we store on our own. Although again, it's the brain doing its job. It's not a terrible thing. But this is one interaction that I think is we're going to be talking about a lot in the future.

We see something that's very similar with GPS. So that's something where there's systematic research. I'm very directionally challenged myself, so I kind of use my GPS as assistive technology. It lets me get around when I couldn't before. But it is true that in people who have fewer issues with this, you're less likely to form a mental map if you're relying on the GPS. Again, it makes a lot of sense, and that's something that over time is going to affect us taking pictures is, I mean, photos is this whole other sub area too, because what do we do with our smartphones? We take pictures and there's research showing that if you're taking pictures during an experience, you're less likely to have a good memory of it on your own. And if it's something that a big trip you've been looking forward to, I mean, that's kind of a bad thing.

And by the way, that effect is probably mostly due to the effect of attention. So just fiddling with the phone itself is probably a detractive for us. So all these are things that we can counter for if we know about it. So we have that. But then we do have the ways you alluded to of there's other ways that it improves memory. There's times when offloading is great, so our brains are terrible at remembering to do things at particular times in the future. We're awful, but phones are wonderful at that, so let's let them take that over, free up our capacity to do other things. Photos can be good memory cues. There's research showing that with older adults as well. So that's something as well. And of course for teachers, it is the ultimate tool for retrieval practice, right? There's all these great things and great technologies,

Eric Mazur:

Which actually brings me to, I think maybe my most important and most burning question. I mean, there's more and more of a talk about striking the right balance between teaching content knowledge and teaching skills. And I remember as a student, and I'm sure that many of our students and you and our listeners will in their education have taken courses in disciplines that they're ultimately not active in. And if I think back of the many courses I took even in my discipline, but in a subfield of my discipline that I'm no longer active in, I would probably not pass an exam anymore, maybe to the shock of some of my colleagues. But that's fine. I challenge them to take a test outside of their area of expertise, and I have trouble remembering. So I think in a sense, if we think about what content knowledge is important, I think it really depends on the career trajectory of our individual students, which of course are very varied.

And I think that that makes it very difficult for us as instructors to think this is the core content knowledge that my student needs to know. I was recently teaching a workshop, and there were some mathematicians who were absolutely convinced that even doctors or politicians should know a minimum of mass, even though it was probably not relevant to these people's work. Let's say you're a doctor in the emergency room. Does it really matter whether or not you can integrate or differentiate the polynomial? I would say probably not as much more important that you know how to get a patient who is brought into the emergency room live out again. And suppose that someday it turns out that taking the derivative of a polynomial is important. Then you can look it up. And here's my argument. If you look it up often enough, you'll remember it simply by virtue of having looked it up many times successively. So I think that memory is also to, in some sense, dictated by how often you need and how crucial the information is for whatever it is that you're doing. Perhaps it's a mere survival, as you said, or finding your way on a map. Unfortunately, I think one of the things we do in education is we say, if you want to graduate from college, you must have this content knowledge. Do you think we still need to continue to have that attitude in an age of mobile devices, ai, the internet and other technologies,

Dr. Michelle D. Miller:

Right? Oh boy. There's several interconnected issues there, and some of them, they really are. They're more about the systems and the culture of higher education, which changes gally slow. Actually, I think glaciers are changing a lot more rapidly right now than higher education's culture. But I mean, that was the big selling point a hundred plus years ago of like, well, sure, learning Latin and ancient Greek, you're not going to necessarily converse with people. But definitely you need that because it will exercise your brain. And quite frankly, what I suspect too is the gatekeeping, right? The gatekeeping culture. So is very clumsy way of saying, okay, well, we only want students who have a certain background or have the ability and privilege to work through these problems, or they've encountered them before, or yeah, there may be some people for whom polynomials are interesting and come to them more naturally, and it just becomes a way to exclude everybody else.

Maybe it makes life easier in the short term, but that's not what we got into education to do. We got into education to have more people be able to step into the fields and the skills, and frankly, the life dreams that they have. So I think that when I say there's some interconnected issues there, that is what I mean. And of course, I wouldn't want us to go back to that system, and I usually push back if I hear some variation on it of like, well, let's make some more math prerequisites because our students aren't doing well in X, Y, and Z. It's like, I don't think that's going to take care of the problem. And I'm picking on math here, but there's definitely other examples. I think now there's a lot more sophisticated systems we're saying, you know what? Yeah, if medicine is your dream and O chem is running over you like a steamroller, we can step in and we can help.

At the same time, there's foundational knowledge and chemistry that, yeah, I think that we can as experts, if we step back and reflect very mindfully and say, yeah, this is really important to understand and to know, don't dive for your phone every time you need to know this thing. But you're right. And that's the other challenge of higher education, especially now with a more rapidly changing world, is we are preparing students for lives and careers that we can't predict and they can't predict because they might not even know what those are yet. So yeah, I think it's an ongoing part of the practice of a very reflective teacher who cares about their students to say, well, okay, let's recalibrate every so often and say, okay, my good faith effort is to prepare you to go on in this field. I'm going to be clear about that.

It's going to have some benefits for these other things you might want to do, and it's going to be inherently interesting. And if I want you to succeed from here on out in that, what are the things that I need to be able to simply ask you? And you simply know. And maybe it's not even difficult because now it fits into this interconnected web of knowledge and it just becomes very easy. I mean, for the looking it up part though, I don't know, I might push back on that. I tell folks my little story of retrieval practice where we bring things back, effortfully out of memory, I was issued an ID number when it came to work at NAU nine digits. I went 23 years with that number, and I looked it up every time I needed to fill it out on a form. And I thought, well, that's impossible. I'll never remember it. And then I bought a parking permit. I needed to key it in. I'm like, oh, okay. I'm going to retrieve it effortfully. And it took me two days and now I know that number. So I mean, it depends on what you're doing when you're looking it up, let's put it that way. Maybe we can agree to semi disagree on that point.

Eric Mazur:

Yeah. But you mentioned something really important, the instructor saying it is important for you to know this. The problem with that state, whenever I hear people say that, and I often fall into this trap myself too, is that I protect my own experience onto the students. It's important to know if you're going to become a chemist or if you're going to become a physicist or if you're going to become a psychologist, but it may be totally irrelevant to your career as a name something. So I think that whenever we hear instructors say, this is important to know, it will behoove us to ask why and for whom. Obviously for us it does. But who knows, as you said, justly, we're educating students for a society that's changing faster and faster. Now with generative AI at the beginning of the semester, I no longer know where I'll be at the end of the semester.

It is frightening how fast technology is developing technology that is impacting, I think, thinking skills at a much higher level than just memory. It's just absolutely amazing. You mentioned something else that was really interesting. You said the glacial pace at which changes. There was one quick thing that our listeners could implement based on it is frighten research. What would that be? I think that many of our listeners will agree. So we're preaching to the choir here. So one of the things that I tend to do at the end of all of my podcast, because we're getting close to that time here, is to ask if there was one quick thing that our listeners could implement based on your research, what would that be?

Dr. Michelle D. Miller:

Oh gosh. One quick thing. Bring in low stakes opportunities for retrieval practice. And so this doesn't have to necessarily even be a quiz. It can be, and we do have these wonderful all kinds of apps. It can run on student's own mobile devices, but it can also be really low tech. It can be as simple as saying, alright, write down everything that you remember from last week and jot it down on a sheet of paper or tap it out on your phone, turn to your neighbor and see if you remember the same things, which would be interesting to, you'd see full circle, like that project you were talking about earlier of do we even remember the same things happening in class? And it becomes social, which is such another way to make memory really compelling. So yes, find those opportunities to reflect, and especially if you can map those onto areas of your course where you are in that position of just solemnly saying, this is very important, but you haven't demonstrated that to the minds and the brains of the students.

So just saying the words isn't necessarily going to do it. So find those opportunities and say, is here where a quick quiz, a little quiz game might be good? Is this where students have an opportunity to try actually a very challenging quiz or challenging set of questions that are really hard, but hey, nobody's grades or their future life is on the line. So it's a good opportunity to maybe fail and see how we can do better. So finding those opportunities for effortful retrieval that work for you, that mesh with your style and are going to have hopefully a little bit of a fun factor because many of us we have, we've had these bad experiences with memory memorization and educational experiences that are perceived as hard or challenging or rigorous. And if it's skills that students are need, if you're like, really, this is not an information heavy course, there's still skills. And in that case, do what so many experts have all zeroed in on and said, well, are students actually practicing the skills you want them to have? And so very similar to retrieval practice, that's the opportunity for students to actually take their brand new knowledge and skills out on the road, take it out for a spin and see if they can really keep it there.

Eric Mazur:

Wonderful. Well, I would like to conclude by thanking our listeners for joining us and thanking our guest, Dr. Michelle Miller. Thank you so much for joining us today.

Dr. Michelle D. Miller: It was my pleasure.

Eric Mazur:

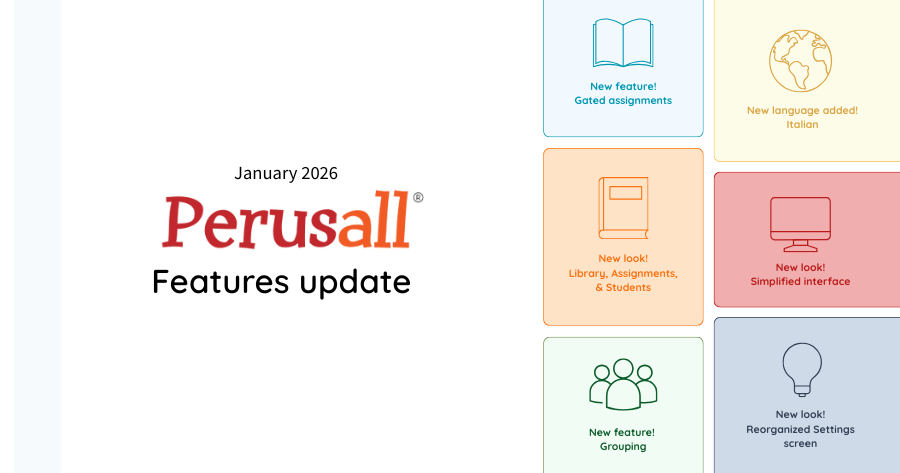

Michelle's book, Remembering and Forgetting in the Age of Technology, is available from West Virginia University Press, and you can order it online for Amazon. But if you're listening today, I have some really exciting news for you starting on Monday, February 26th, 2024, you can join Perusall and West Virginia University Press for a four week asynchronous communal reading experience of Michelle's new book. This is an author facilitated events. So for a nominal fee, you'll not only get access to the book, but you'll be reading and interacting with the author and other like-minded educators like me, for example, brainstorming, how to balance the use of technology to the classroom. To learn more, go to perusall.com/engage. And finally, you can find our Social Learning Amplified podcast and more on perusall.com/sociallearningamplified altogether. Subscribe to find out about other episodes. I hope to welcome you back on a future episode. Social Learning Amplified is sponsored by Perusall, the social learning platform that motivates students by increasing engagement, driving, collaboration, and building community through your favorite course content. To learn more, join us at one of our introductory webinars. Visit perusall.com to learn more and register.

.png)